Felice Beato (1832-1909): Conflict and Commerce

By Andrea Stern, ASA Ltd

For many Westerners, their first and sometimes only impression of China, it’s people, traditions and landscapes, came from the images taken by an Italian-British photographer, Felice Beato (also known as Felix Beato). He was born in Venice c.1832 and little is known of both his early and of his last years. Until his death certificate was found in 2009 it was thought that he had died in Burma in the late 1890s, but the certificate reveals that he died in Florence on 29th January 1909. We also know that he remained a bachelor, and early in Beato’s life his family moved to Corfu, a British protectorate, which enabled him to claim British citizenship.

Beato was a commercial photographer with many books to his name, a teacher, a pioneer of photographic techniques, a great traveller, a dealer in imported goods and a property consultant. But war seems to have held a fascination for him and he is considered by some to be the most significant war photographer of the 19th century[1] as well as an early chronicler of the Far East and Middle East. His images of the people, culture and architecture formed a first and lasting impression of these far-off areas of the world that many in the West would never visit. They are often all that remains of many buildings which no longer exist.

His war photography career began when, through his connections to the British Army, he and his partner, brother-in-law James Robertson, were commissioned to replace Roger Fenton and arrived in time to photograph the fall of Sebastopol in 1855. The partners went on to Calcutta in 1857 to document the aftermath of the Indian Rebellion and then made their way to the Holy Land, Syria, Malta, Egypt, then to China, often accompanied by Felice’s younger brother, Antonio Beato.

His images of the Second Opium War, China 1860, were the first to document the progress of a military campaign. Unusually, and believed to be for the first time, Beato’s photographs show human corpses on the battlefield and Beato, an inventive and creative professional, would go to great efforts to restage battle scenes in gruesome detail to evoke the horror of war in a realistic and dramatic manner.[2]

His images of the Second Opium War, China 1860, were the first to document the progress of a military campaign. Unusually, and believed to be for the first time, Beato’s photographs show human corpses on the battlefield and Beato, an inventive and creative professional, would go to great efforts to restage battle scenes in gruesome detail to evoke the horror of war in a realistic and dramatic manner.[2]

However he only photographed enemy corpses, even unearthing some in Lucknow, India, that had already been buried. Perhaps it is this approach to his work in China together with his images of events during the Indian Rebellion of 1857 that have been thought of as the first substantial body of photojournalism.

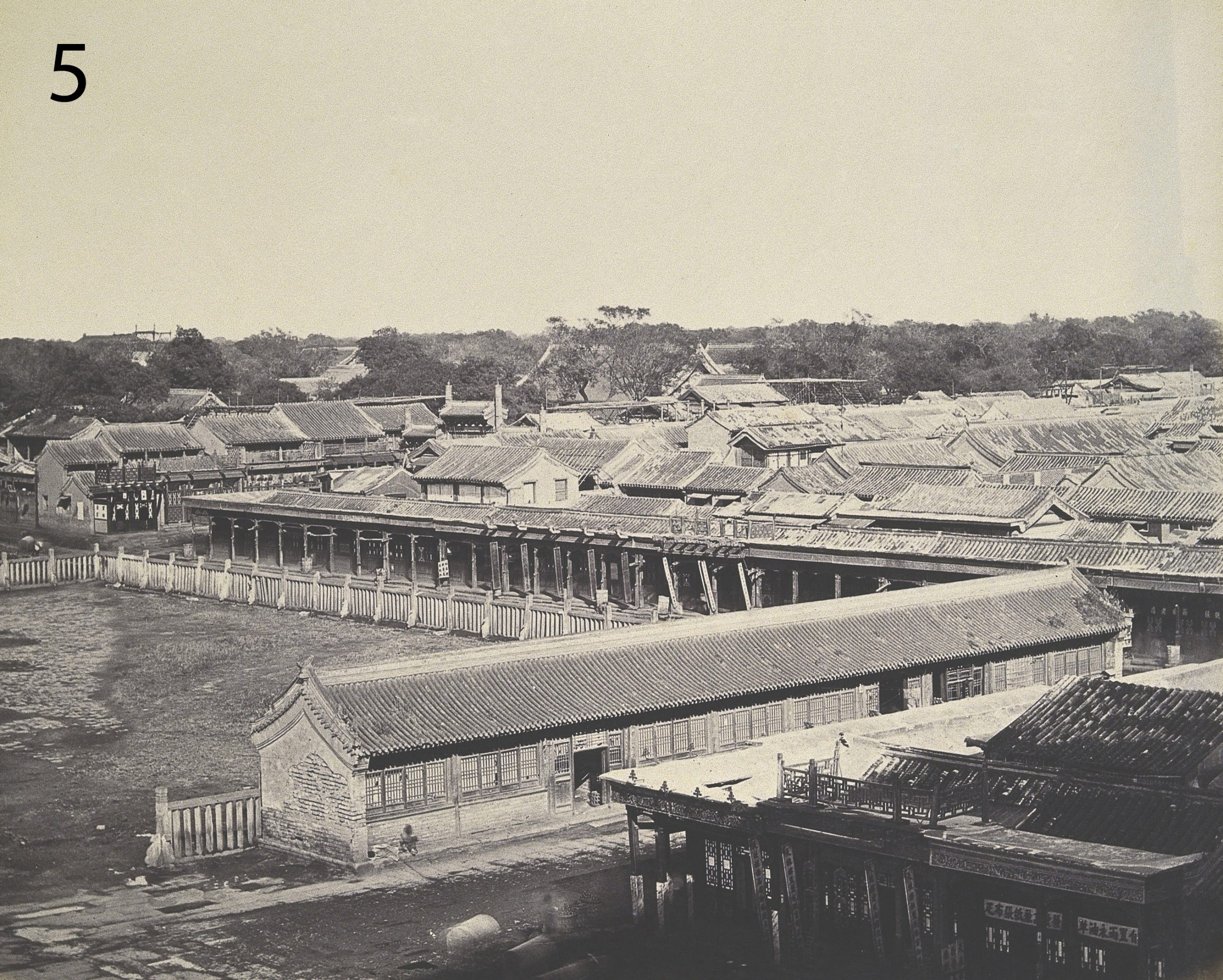

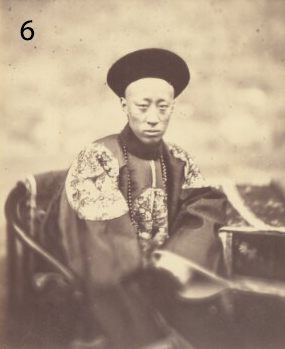

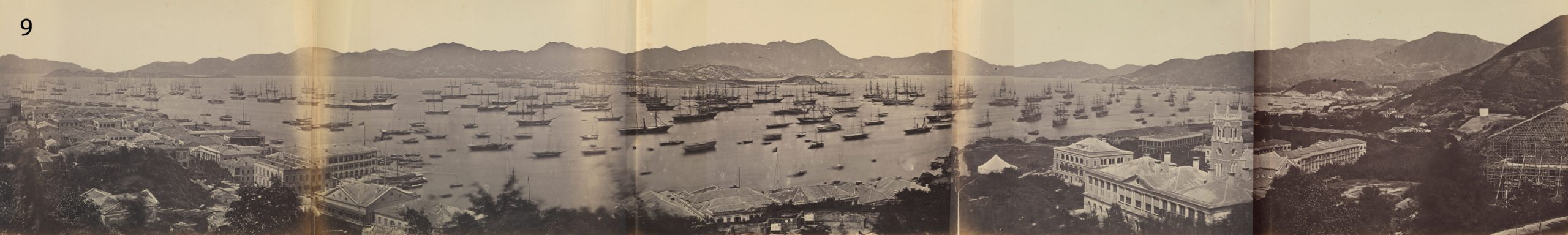

Although Beato never lived in China for any length of time, as he did in Japan and Burma, Beato created one of the earliest comprehensive photographic views of China that has survived. He took some iconic images of the Old Summer Palace at Qingyi Yuan, the Emperor’s private estate. Many of the buildings there were plundered and burnt by Anglo-French forces on 6th October 1860, and Beato’s images, probably the only images to be taken inside the palace, have become the earliest known record of them and are ‘of the utmost historical and cultural importance.’[3] Beato also photographed Lord Elgin and Prince Kung the signatories to the Convention of Peking on behalf of the British Government and the Xiangeng Emperor respectively. Whilst in China Beato also travelled briefly to Hong Kong photographing the city and taking some of the earliest photographs ever taken in China.

After China, Beato returned to England in 1861, before taking up residency in Yokohama, Japan, from 1863-1884. Beato only set out again for a war zone once during his stay in Japan, as the official photographer with the USA naval expedition to Korea in 1871, taking the earliest authenticated images of that country. His last war commissions were with the Nile Expedition to Khartoum, Sudan, 1884-85, to relieve General Gordon. The mission was unsuccessful but he was able to document the Expeditionary forces retreat. In 1886 he was in Burma, recently annexed by the British, and in time to capture on film British military operations at the Royal Palace during the fall of Mandalay and the seizure of Burma’s king, as well as photographing insurgency soldiers and prisoners. Being a war photographer it’s not surprising that he was on occasion in the crossfire and one source records that he narrowly avoided an assassination attempt by declining an invitation to a post-breakfast excursion. The officers he would have been with were all killed by a group of samurai, one of which was caught and publicly executed.

Beato naturally photographed this and later returned to the scene of the crime with a friend, artist Charles Wirgman, to recreate the event.

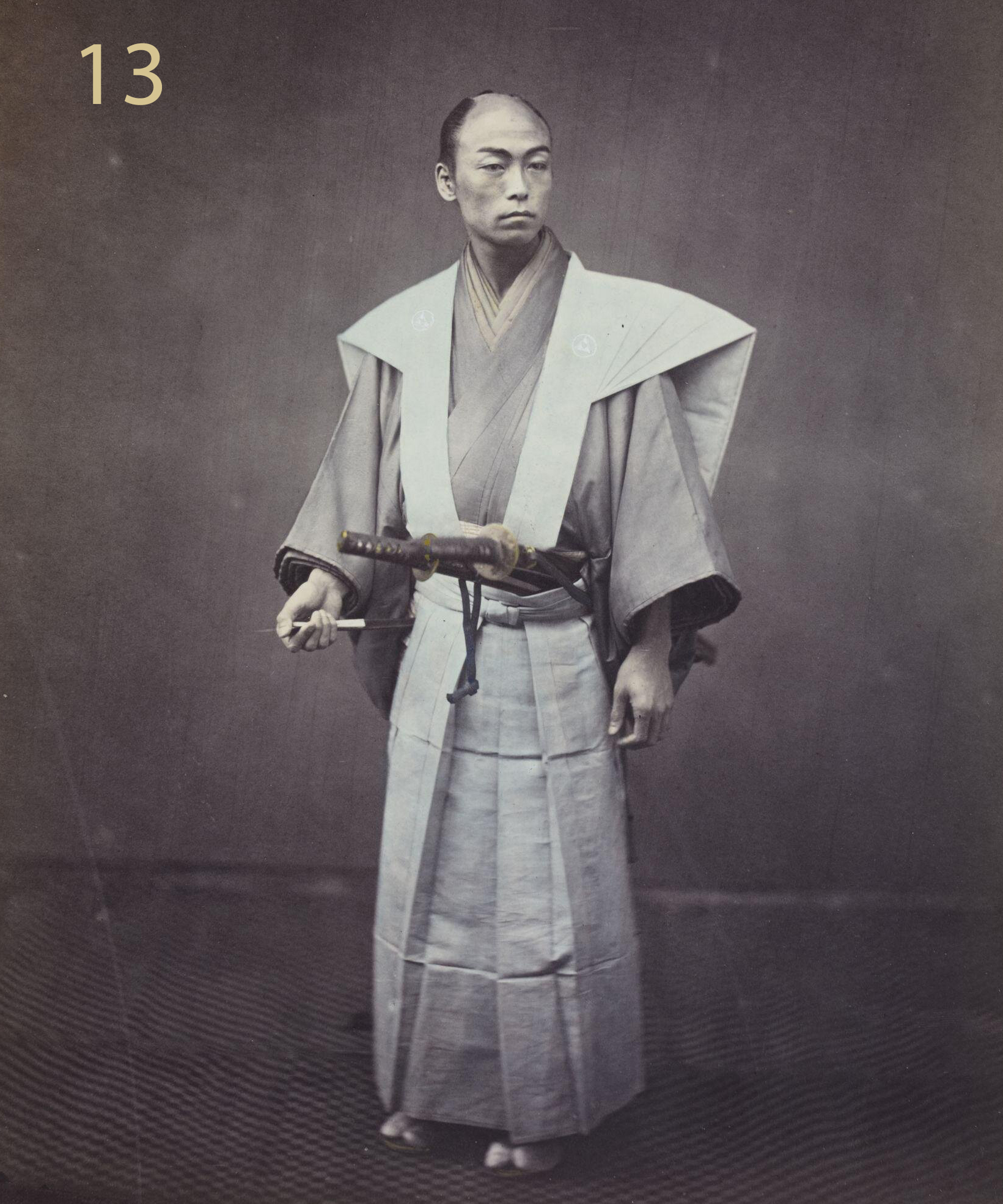

When Beato moved to Japan in 1863 he began a new phase in his work. People were generally absent from his previous images, which celebrated the might of the British Empire, except for a very few portraits, and as corpses on battlefields. Once in Japan he began to photograph the people, panoramic landscapes and city views.

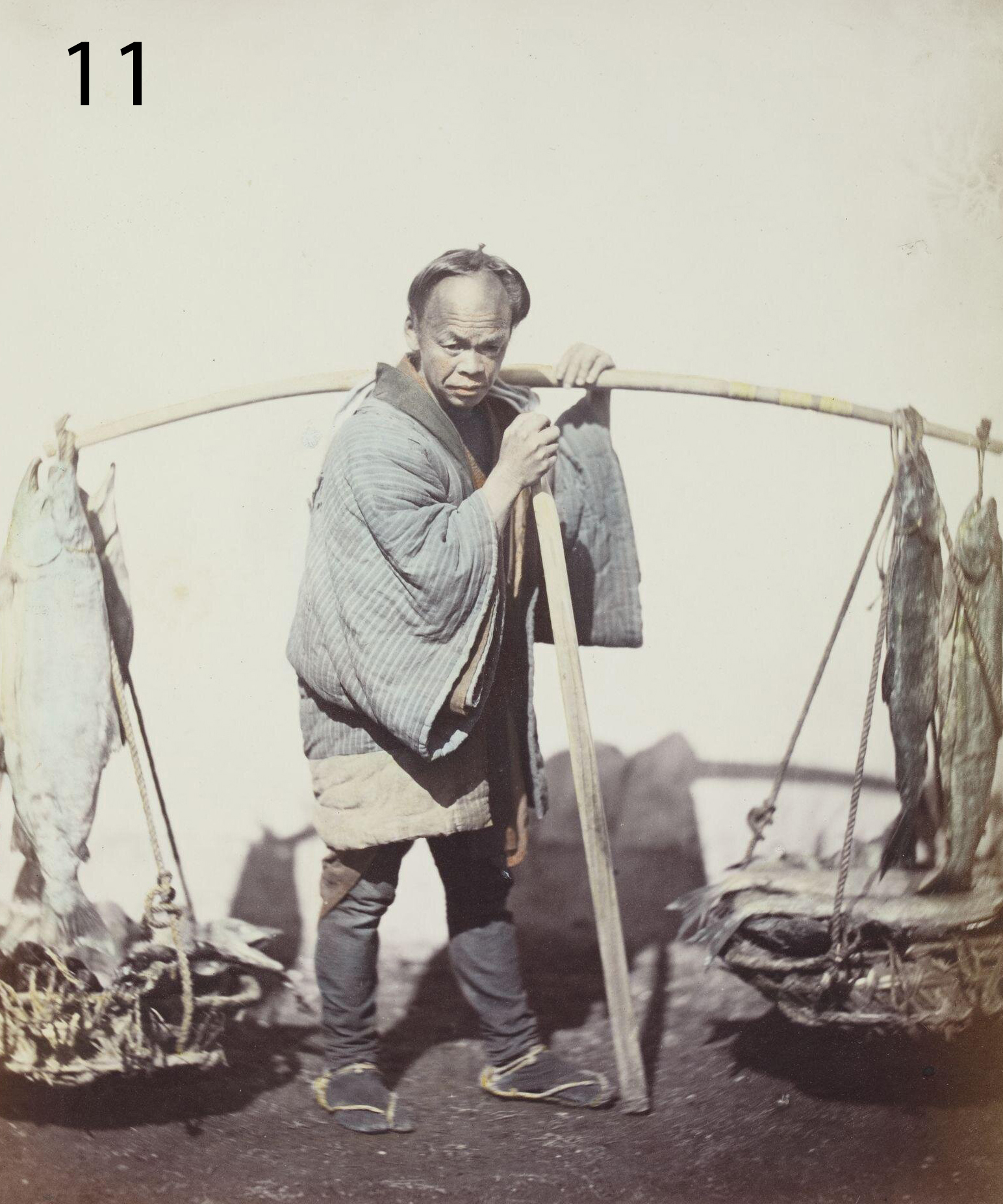

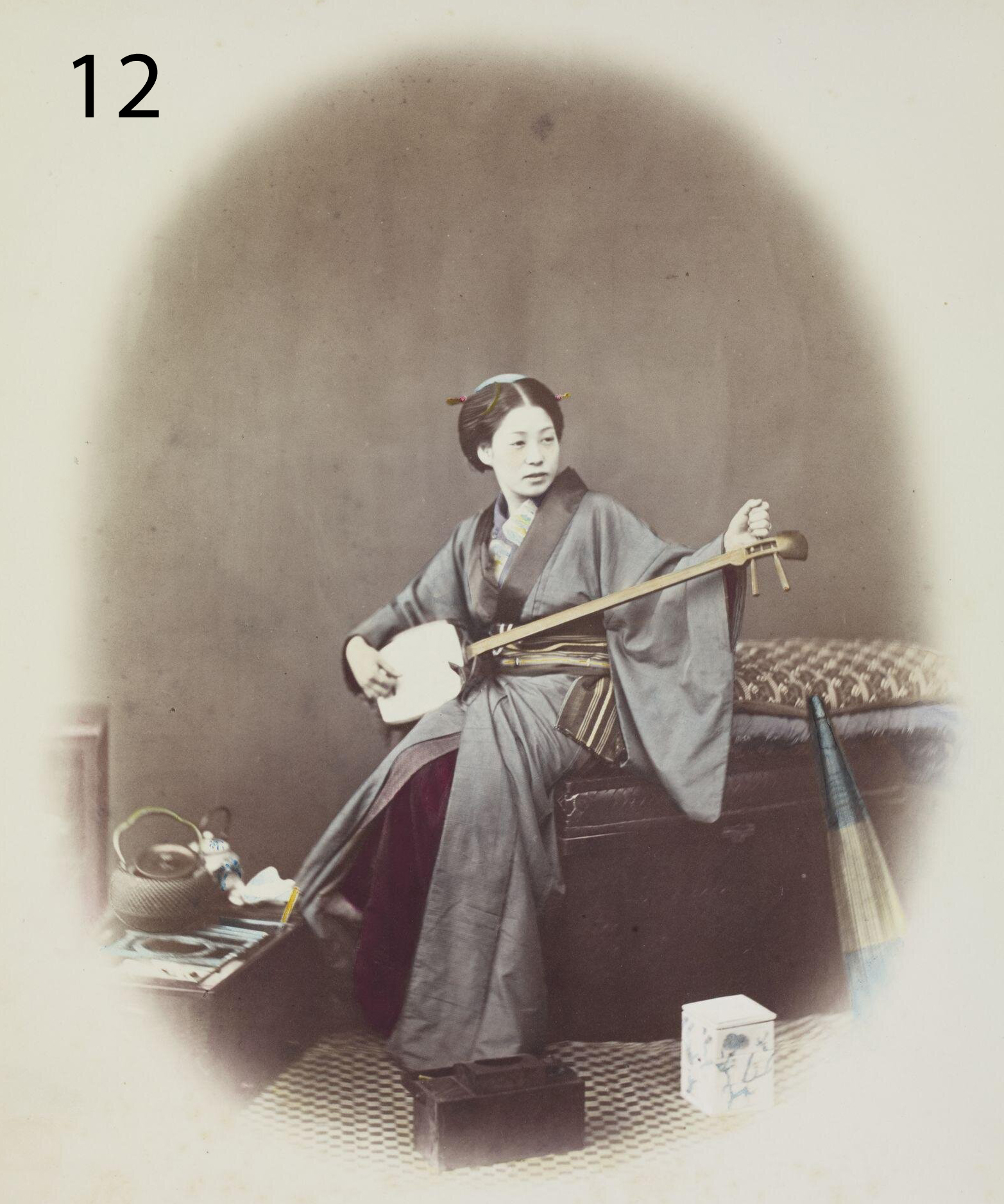

Beato was very commercially-inclined and had sold a large number of individual prints during his stay in England in 1861. Now in the Far East he started to create albums, first allowing customers to make their own selection and then, realising the commercial potential, he made his own selections of people, their traditions and panoramic views, a combination which became very popular. His first published album Photographic Views of Japan with Historical and Descriptive Notes shows his change of style of photography catering more to the foreign merchant and developing tourist trade. This album of photographic portraits and panoramas, each ac companied by descriptive and informative (though not always accurate) captions, could perhaps be considered a prelude to the ‘coffee table book’. As a businessman he also knew how to appeal to his customers’ tastes. His panoramas were spectacular and comprised several images seamlessly joined together; for example, the complete version of his panorama of Pehtang is made up of 7 photographs and is over 7 meters in length. He also produced a series of photos of people from different walks of life on the Tokaido Road (running from Kyoto to Tokyo) which catered to foreign curiosity about the ‘exotic’ Japanese.

companied by descriptive and informative (though not always accurate) captions, could perhaps be considered a prelude to the ‘coffee table book’. As a businessman he also knew how to appeal to his customers’ tastes. His panoramas were spectacular and comprised several images seamlessly joined together; for example, the complete version of his panorama of Pehtang is made up of 7 photographs and is over 7 meters in length. He also produced a series of photos of people from different walks of life on the Tokaido Road (running from Kyoto to Tokyo) which catered to foreign curiosity about the ‘exotic’ Japanese.

Although he lost his studio and most, if not all, of his negatives in a fire that destroyed most of Yokohama in 1866, within 2 years Beato had rebuilt his studio and by 1870 album sales had become the mainstay of his business. In fact so much so that he took on other enterprises including importing carpets, a property consultancy, as expert witness for the court, and he was also appointed Consul General for Greece in Japan. He also owned several studios, where he pioneered and refined photographic techniques, in particular naturalistic hand-colouring and expanded panoramic imagery.

Beato predominantly produced albumen silver prints from wet collodion glass-plate negatives. Given the limitation of the technology of the times and the weight, amount and fragility of equipment and the pure water he needed to carry with him to create and develop his negatives, Beato’s images are remarkable for their quality and naturalness as well as for their unique subject matter. With access through his British military contacts Beato was able to travel to remote parts of Japan and later Burma, and photograph both the amazing and as well as the darker aspects of life. The first volume of his album Photographic Views of Japan was in black and white, but in the second volume, with his understanding of market trends, his portraits and everyday life scenes were coloured by hand in delicate colours. Beato worked with a number of Japanese watercolourists trained in colouring woodblocks for traditional prints and their skills and techniques were adapted to photography. His photographs were reproduced in many newspapers and travel publications throughout the world into the 20th century and contributed greatly in shaping the image of the Far East for many in the West.

He retired from photography in 1877, selling his stock, whilst continuing his other business interests. But after a short spell in Sudan he eventually arrived in Burma in 1886 where, ever the commercial businessman, he set up a studio and an antiques dealership. By the end of the 1890s Beato had again shaped the image of a Far Eastern nation for the western world.

GSPA continues the tradition of Beato by showcasing a shared Chinese culture from the lens and perspective of photographers worldwide.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~

[1] Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China, 1842–1860. London: pp. 292–295. Bernard Quaritch, 2009. ISBN 0-9563012-0-7.

[2] Lacoste, Anne. Felice Beato: A Photographer on the Eastern Road, p.10. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2010. ISBN 1-60606-035-X.

[3] Terry Bennett, (ibid)

Images, Captions and Credits:

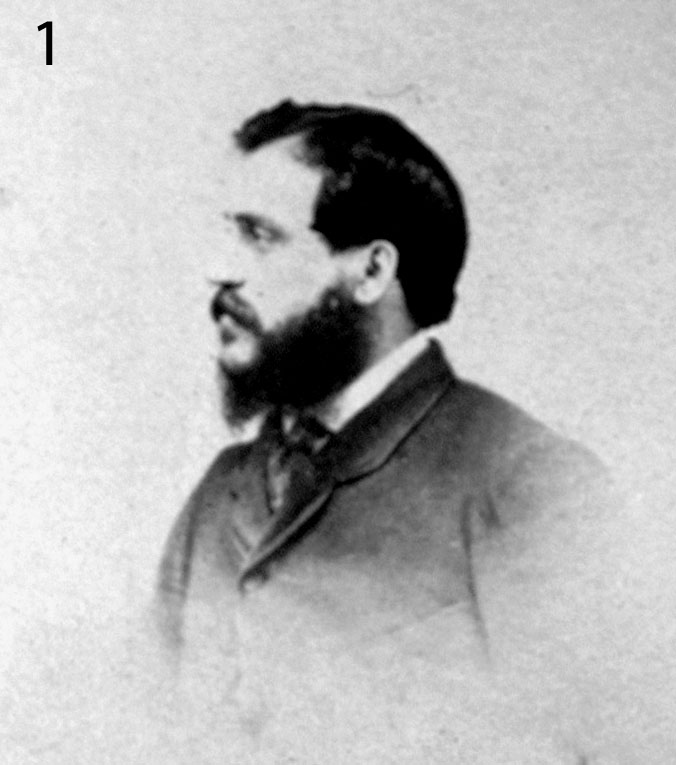

- Felice Beato, unknown photographer (possibly a self-portrait)

- Damage from an enemy mine sprung in the Chutter Manzil, Lucknow, Indian Mutiny, 1857. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2017JX4098

- Interior of the English Entrance to North Fort on 21st August 1860. V&A 2015HV7872

- View of the Imperial Summer Palace, Yuen Ming, showing the Pagoda before the burning, Oct 1860. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2015HV7829

- View of the Forbidden City, Beijing, at the time of the Second Opium War, 1860. Photo, Felice Beato. Wellcome Institute V0037640

- Portrait of Prince Kung, Brother of the Emperor of China, shortly after signing the Convention of Peking on behalf of the Qing Dynasty, with Lord Elgin, November 4, 1860. Photo, Felice Beato.

- Pavilion on Water, South China_LACMA_M.83.302.49

- General Store-Office in City of Song, Tiang, Province of Wu, China_LACMA_M.83.302.58

- Panorama of 5 views of Hong Kong showing the Fleet for North China Expedition, March 1860. Photo, Felice Beato. Wellcome Collection

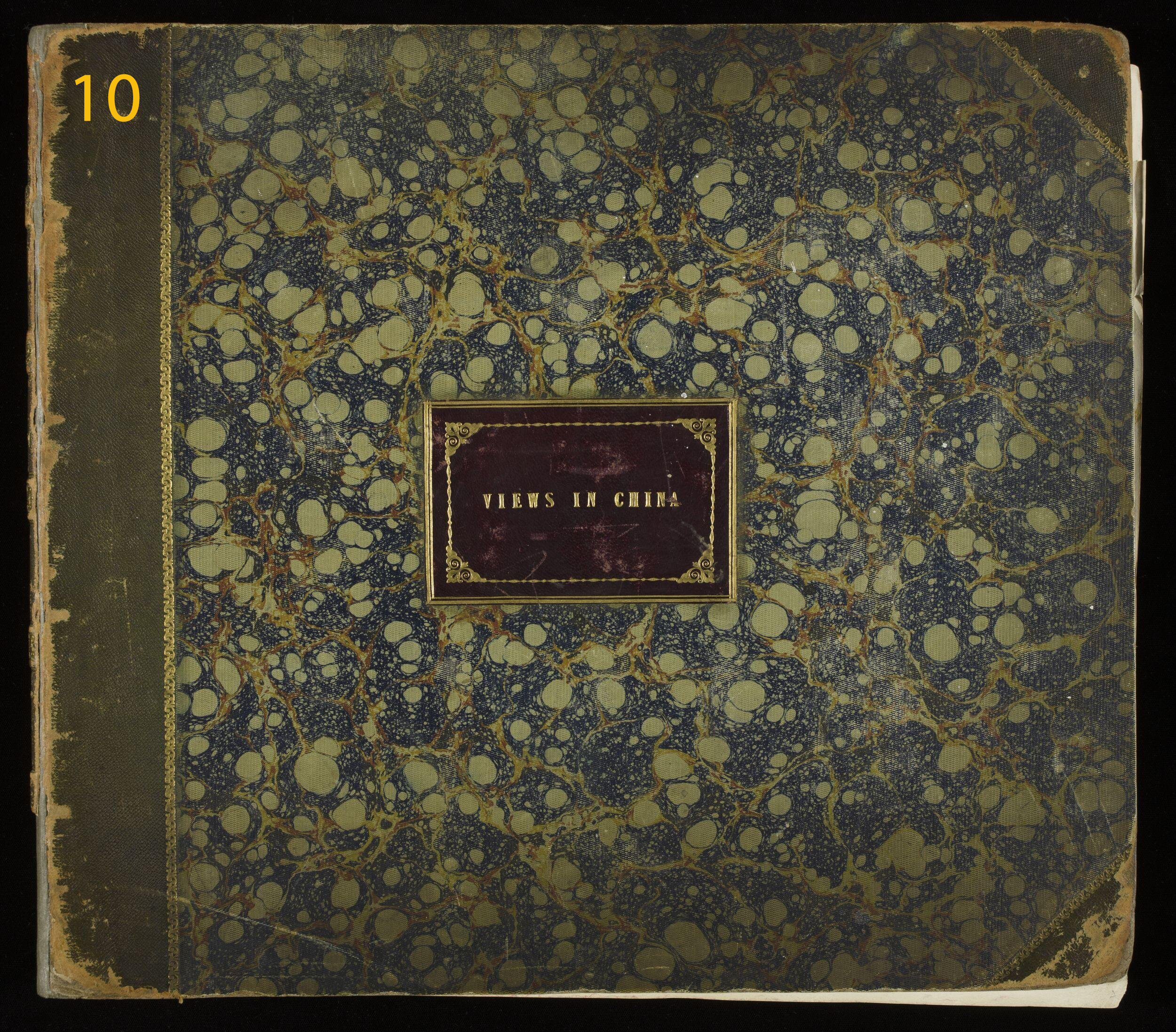

- Views In China, Album, 1860. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2015HV7663

- A fish seller Views of Japan, 1868. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2014HC3937

- ‘The Belle of Yokohama’, Girl Playing the Samisen, Views of Japan, 1868. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2014HC3900

- Japanese high officer in court attire, Views of Japan, 1868. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2014HC4014

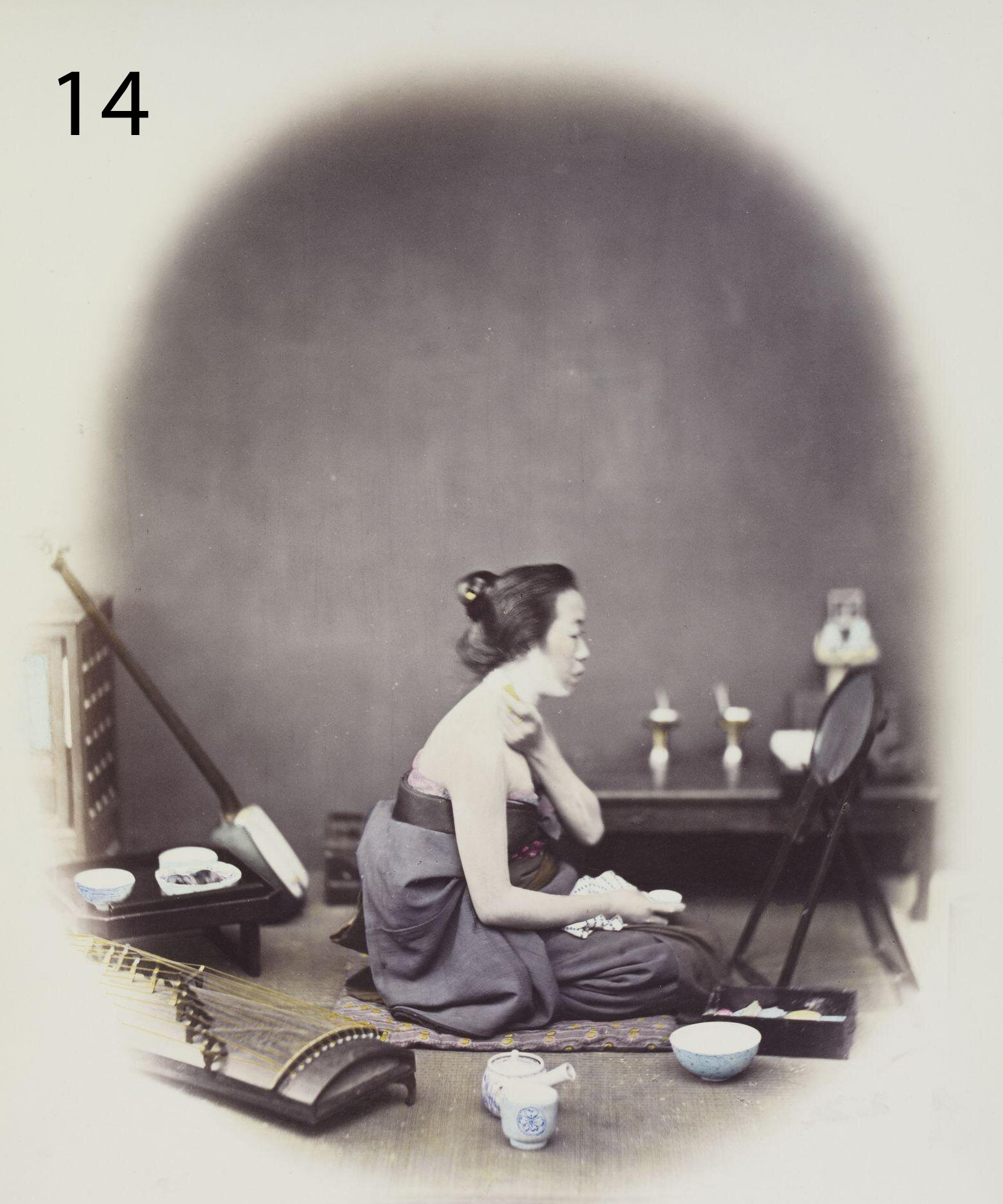

- Japanese girl at her toilet, Views of Japan, 1868. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2014HC3986

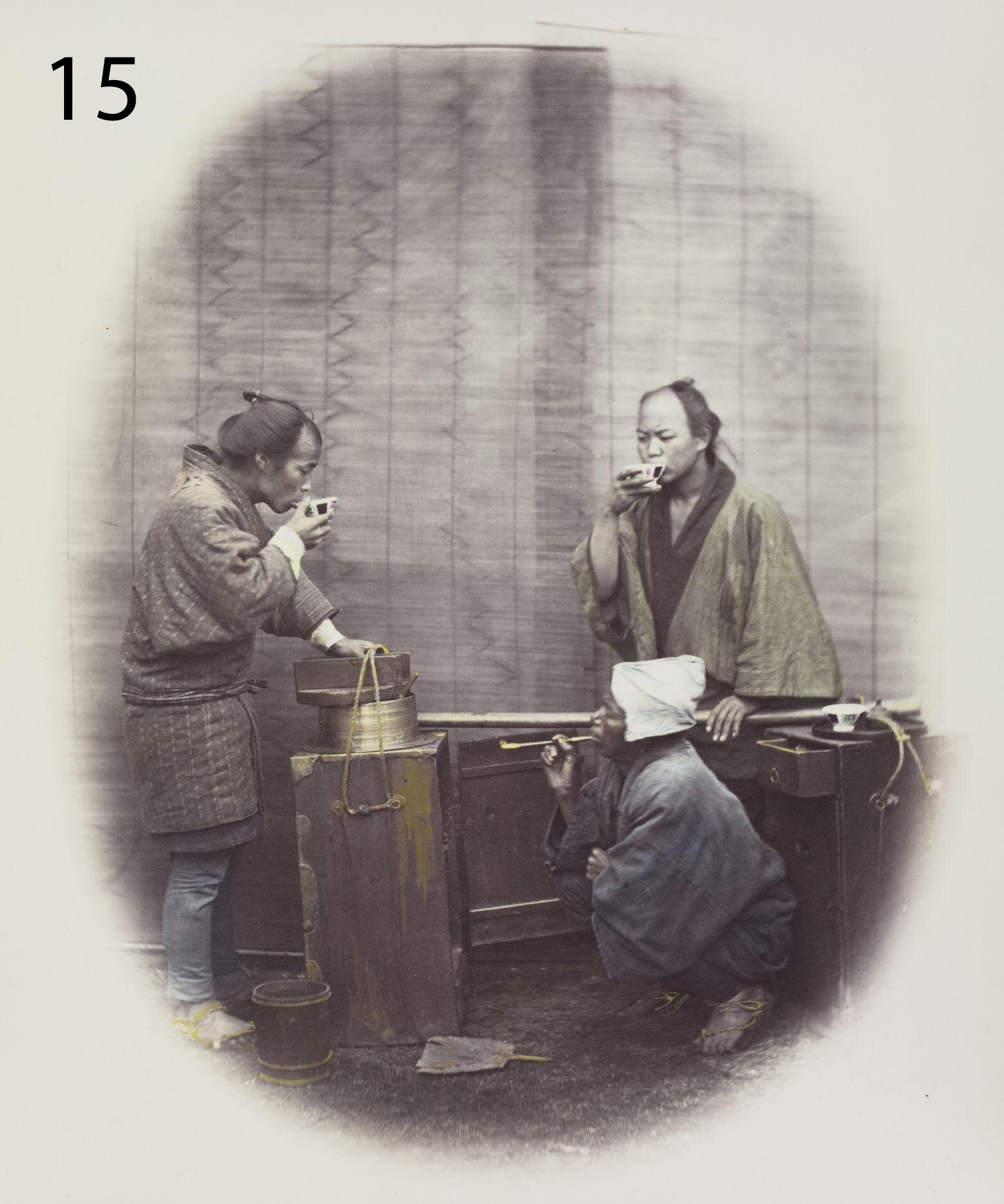

- People at a tea stall, Views of Japan, 1868. Photo, Felice Beato. V&A 2014HC4020

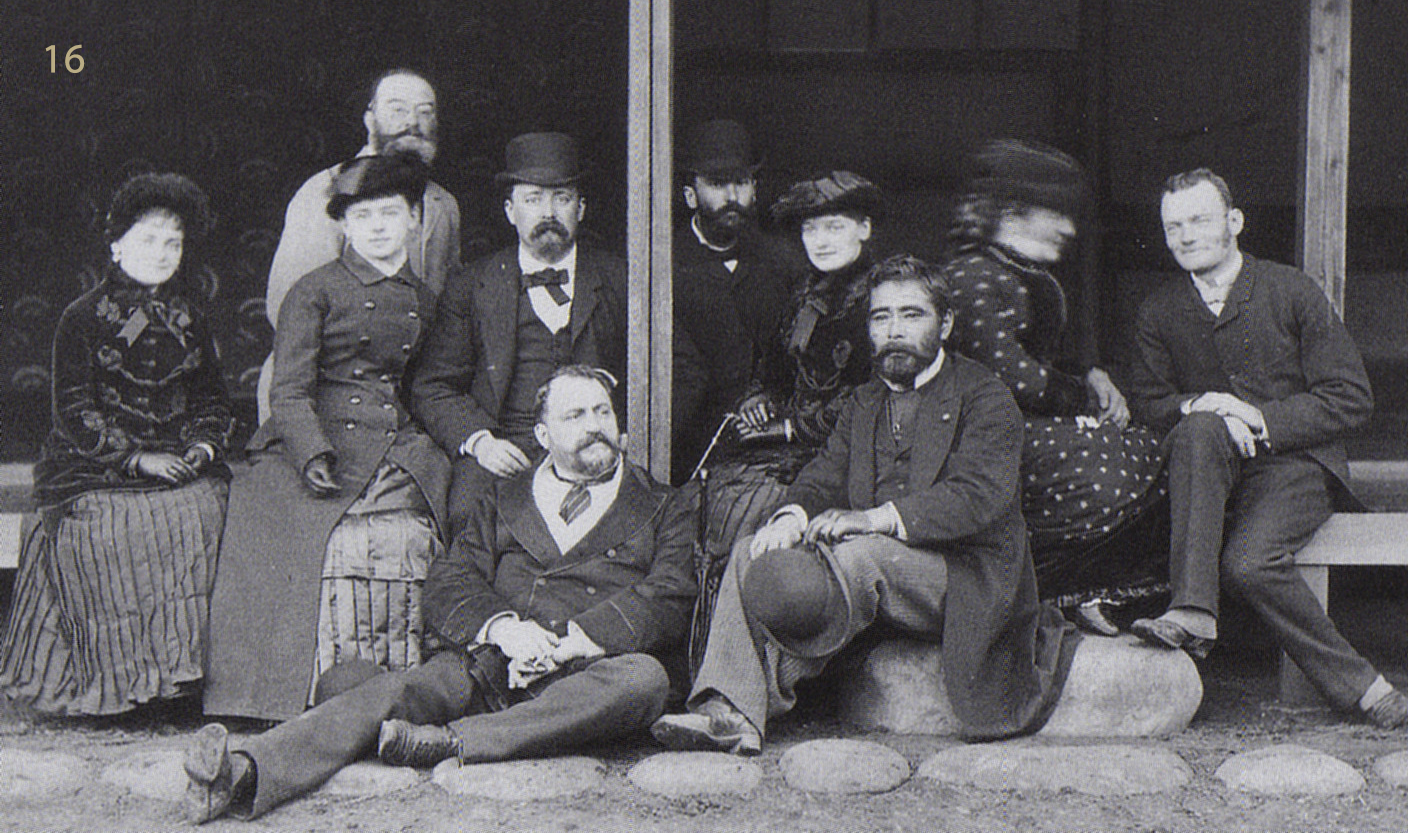

- Felice Beato (front left) with Saigo Tsugumichi, Japanese Admiral and politician, (front right), and foreign friends, 1882. Photo, Hugues Krafft (1853 – 1935)

References:

https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/beato_people/fb2_essay01.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felice_Beato

https://www.all-about-photo.com/photographers/photographer/1394/felice-beato

https://www.getty.edu/art/collection/person/103KJ0

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283169

https://www.ranker.com/list/felice-beato-photography/cleo-egnal